HUMAN RIGHTS WORK

Early Influences

Guatemala, 1988 (Photo by Shanee Stepakoff)

The seeds of my commitment to promoting human rights and social justice were already present during my high school years. In my junior year, I began compiling news reports about the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, which had just ended, and I wrote letters and organized programs advocating for Cambodian genocide survivors in particular and Indochinese refugees more broadly. As an undergraduate, I minored in sociology at Clark University (where I graduated magna cum laude, with Highest Honors in psychology, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa) and then completed a second Bachelor’s degree, in urban studies, at Worcester State College. The latter program included coursework in areas such as housing, criminal justice, ethnic identity, and social change.

My first full-time job after college (1984-1986) was as the Special Projects Coordinator for the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless. I wrote grant proposals to fund homeless shelters in the Worcester region, several of which were successfully funded, and I developed a clearinghouse through which people could donate unneeded furniture and household items to be stored and then delivered to people who were transitioning from shelters into permanent housing. Additionally, I completed a 6 month internship in San Francisco, with the Breakthrough Foundation Youth at Risk Program, a program that brought together members from different youth gangs in an attempt to build resilience and reduce community violence. During that period, I also volunteered as an English-as-a-second-language teacher for the Cambodian Refugee Women’s Project, a project that sent native English speakers into the homes of refugees who had recently arrived in the Bay area and knew little or no English.

(For information on my documentary film, Threads, to be released in the spring of 2019, which traces the life of one of these women over the course of more than 18 years, please refer to the “Threads Film” tab on this website.)

The truly formative experience that shaped the course of my work and my life occurred in a manner that I could not have predicted. After seeing a documentary film entitled “You Got to Move”, about Myles Horton and the Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee, I made arrangements to visit Highlander, a center that had brought together people of all races during the era of racial segregation in the United States and that has continued, since that era, to train leaders in the skills needed to promote human rights and social justice. Highlander had played a critical role in the U.S. civil rights movement, training Rosa Parks and many other activists. During the few days I spent there, I had the good fortune to meet Myles, who by chance had just returned from a visit to South Africa. When Myles heard that I was planning a trip to South Africa, coordinated by the Organization Development Institute, to study the dynamics of large-system change, in conjunction with an alternative Master’s degree program I had enrolled in under the mentorship of Dr. Jack Gibb (a pioneer in the study of group dynamics and organization development), Myles encouraged me to connect with Reverend Dale and Tish White.

Dale and Tish were the co-directors of Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre, an ecumenical anti-apartheid center near Johannesburg that was also a residential community, in which people of all races lived and worked together, in direct defiance of South Africa’s Group Areas Act, a law that prohibited people of different races from residing in the same residential area. From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, WFC had had a department called PROD (Personal Relations Organization Development), which conducted T-group trainings to promote interracial dialogue and self-empowerment, based on a model that was originally developed by the NTL Institute in Bethel, Maine. In the apartheid era, WFC was one of relatively few places in South Africa where people of different races could meet and participate, together, in small-group experiential learning. As noted by one of the interviewees in Vanek’s (2005) chapter, “these courses provided many anti-apartheid activists with a way of seeing the humanity in people of different racial groups. It was a powerful experience precisely because a person’s habitual way of relating to people and perceiving people was challenged.”

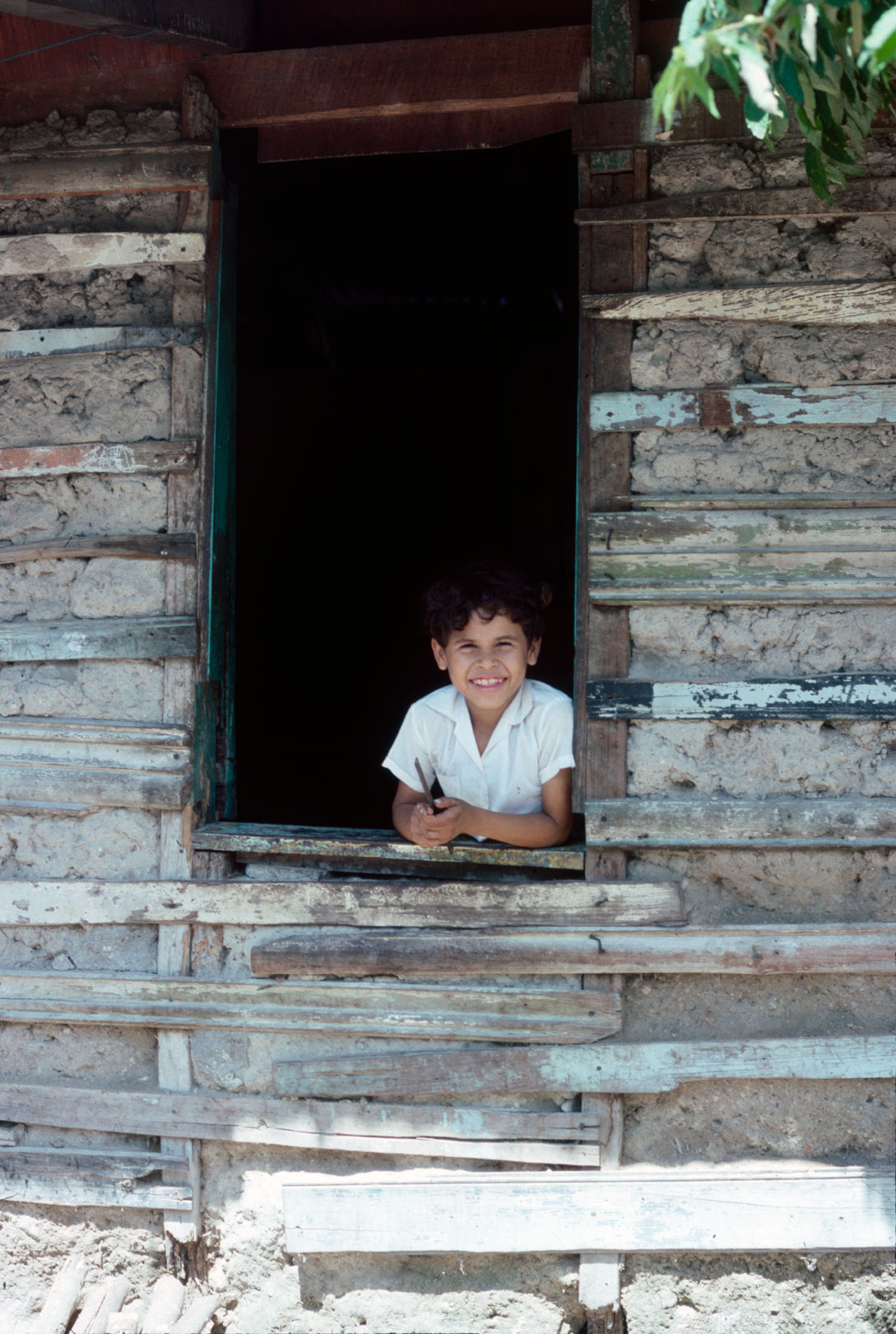

El Salvador, 1988 (Photo by Shanee Stepakoff)

WFC’s PROD programs played a role in the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). The BCM emphasized psychological liberation (e.g., the capacity to resist internalized oppression and to recognize one’s dignity and value) (rather than political party adherence/mobilization) as a key component of the Black freedom struggle in South Africa. The PROD courses influenced Steve Bantu Biko, leading him to critically examine his position as a black person in South African society and to recognize the importance of self-definition. These courses have been cited as a factor in the development of Biko’s views on black consciousness, and in particular in his decision to form the South African Students Organisation (SASO) in 1968.

Many of Biko’s friends and associates, including several leading clergymen and proponents of radical Black Theology, an offshoot of Biko’s Black Consciousness philosophy, were associated with Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre. These included Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu, Bishops David Nkwe and Johannes Seoka, and priests Sipho Masemola, Enoch Shomang, Lebamang Sebidi and Stanley Ntwasa, among others. Zephania Mothopeng, one of the founders of the Pan Africanist Congress with Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe and a former Robben Island prisoner as well, had been a director with Wilgespruit’s Urban Resources Centre in the mid-1970s. Wilgespruit’s Urban Resources Centre had programs in Roodeport, Kagiso, and St Ansgars. AZAPO was founded at St Ansgars in 1978, and several AZAPO leaders worked at WFC in various departments, promoting self-help, cooperative development, and workers’ and trade unions’ development.

There were, however, a wide range of ideological positions represented at WFC, including many people who were affiliated with the UDF (a larger political coalition that was active in the 1980s), as well as people who were focused more on personal and spiritual growth and were not affiliated with any political organization.

NTL (National Training Laboratories) Institute for Applied Behavioral Science, an organization then based in Bethel, Maine, which promoted experience-based learning about group dynamics, was involved in a long-term consultancy with Wilgespruit during the period that I was there. I had learned about NTL from one of my urban studies professors (Tuck Amory) as well as from my MA advisor Jack Gibb (who had been one of the first psychologists to develop NTL’s model of experience-based learning, in the late 1940s), but now I had the opportunity to become much more familiar with experience-based learning and group dynamics.

I made an initial visit to Wilgespruit during August 1986, as Myles had suggested, and then returned for a five-month stay from December 1986 through April 1987, living in the home of Dale and Tish and their two daughters, Natasha and Anastasia. My half-year in South Africa coincided with the peak of apartheid repression. President P.W. Botha had instituted the second state of Emergency in June 1986, which allowed the apartheid government to enforce extreme measures to suppress freedom of speech, movement, and organization. Activists – including children and teenagers – were being held in political detention for months at a time, where they were tortured and not infrequently killed. Human rights organizations were being targeted for bombings and raids. In 1986, Wilgespruit was raided by police, and several teenagers who had sought refuge from township violence there were detained and tortured. Benjamin Oliphant, a young activist who was hoping to become an Anglican priest, was picked up by the authorities during that raid, and killed within days, just before I began staying at Wilgespruit. Though I did not meet him, the fact of his death was the beginning of a long awakening for me, and I couldn’t help but notice the ways that his death impacted the entire Wilgespruit staff.

El Salvador, 1988 (Photo by Shanee Stepakoff)

At Wilgespruit, I was assigned to the Urban Community Organizing Division (UCOD), where I had the good fortune to learn from and be supervised by Ishmael Mkhabela. Ishmael, a professional community organizer and community conflict resolution practitioner, was a respected leader in the Black Consciousness Movement and had been president of AZAPO in the early 1980s. (He later went on to serve important leadership roles in post-apartheid South Africa: he is the executive director and trustee of FinMark Trust, chairperson of Johannesburg Inner City Partnership, and Vice-President of the South African Institute of Race Relations. He was a founder and former Chief Executive Officer of Interfaith Community Development Association. He has served as deputy chairperson of National Housing Forum as well as chairperson of National Housing Board, New Housing Company, Johannesburg Social Housing Company, the Steve Biko Foundation, and Roodeport and Soweto Theatres. In addition, Ish is a trustee of Nelson Mandela’s Children’s Hospital and serves on the boards of Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital Trust, Centre for Development and Enterprise, and Donaldson Trust.)

UCOD conducted community organizing courses for activists from the townships. I assisted with a variety of tasks related to these courses, and I also helped to organize a campaign to save the Crown Mines Community, a unique multiracial community that was slated for demolition by the apartheid government.

One of the activities I feel proudest of was having drawn upon my previous experience with the Massachusetts Coalition for the Homeless to help coordinate the first meeting of a group of community and religious leaders from the Johannesburg region who were concerned about the large numbers of homeless people that resulted from the apartheid government’s harsh enforcement of the Group Areas Act and similar racist legislation. This initial meeting became the springboard for The Witwatersrand Network for the Homeless, a regional coalition that constituted South Africa’s “first recorded grouping of poor people to fight evictions and to mobilize for housing for the poor.” Ishmael Mkhabela was the convener. He had established contacts with people who were shack-dwellers (also known as “squatters”) in various locations throughout the region. Using his skills as a community organizer, he had “entered into dialogue with the homeless people to find out what could be done to address their plight…. Mkhabela established that the squatters wanted to be left where they were, not to be moved, and to be provided with essentials such as water…, as well as skills and advice to upgrade the existing accommodation…. Together with the shack dwellers, the Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre was seeking to help the poor people access land and housing….and to participate in decision making at all levels….Eventually, through the Network, some inhabitants of Soweto were able to purchase their own houses…The homeless had been organized into viable communities that were able to articulate their interests….This marked the first initiative by the poor to take control of their own lives through [addressing] housing and land issues.” (The remarks in quotations above are from a Master’s thesis in urban and regional planning, by Sibonkaliso Shadrack Nhlabathi, entitled ‘The Role of Community Based Housing Organizations in Housing Low-Income People’, submitted to the University of Natal, Durban, in 1996.) The Witwatersrand Network for the Homeless received the 1987 South Africa Human Rights Award, selected by readers of The Indicator, a newspaper that had an important role as an alternative source of information during the apartheid era.

(Click to read a summary page from a chapter by Monique Vanek, “Wilgespruit Fellowship Centre: Part of Our Struggle for Freedom”, from the book From National Liberation to Democratic Renaissance in Southern Africa, edited by Cheryl Hendricks and Lwazi Lushaba and published by the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa – CODESRIA – in 2005.)

(Or, click to read Vanek’s entire chapter.)

(Click to learn more about NTL Institute for Applied Behavioral Science.)

Formal Study

Many (perhaps most) of my colleagues in South Africa had been subjected to politically motivated torture. Whereas I had begun with an intention to focus my thesis research on community development and social change, areas that were in line with my urban studies degree and my advisor Jack Gibbs’s academic background, I instead became interested in the question of how people cope with the experience of being in detention: What is it that helps them survive such a harrowing ordeal? Hence, I decided to conduct a qualitative, in-depth study of the experiences and coping strategies of political detainees. My thesis, entitled “Detainees in South Africa: What They Experience and How They Cope”, was used to support torture treatment programs in South Africa, Argentina, Chile, and The Philippines in 1988 and thereafter. (Within South Africa, I circulated the thesis under the pseudonym, K. Wrenn, to protect the confidentiality of the interviewees.) In 1989, my thesis was accepted by The Rehabilitation and Research Centre for Torture Victims (RCT) Documentation Centre and Library, in Copenhagen (Denmark).

Meagan Hyde de Clerck, Sudanese Women

In 1988, I presented my findings at the 96th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, in Atlanta, Georgia. My findings were discussed in the books The Psychological Origins of Institutionalized Torture (by Mika Haritos-Fatouros, Routledge, 2002) and Political Violence and the Struggle in South Africa (edited by Andre du Toit & N. Chabani Manganyi, St. Martin’s Press, 1990).

The interviews I had conducted for this project deepened my desire to understand how people cope during and after ethnic and political violence. I was able to redesign my MA program to focus on political psychology rather than organization development. I went on to conduct interviews with families of the disappeared, and human rights defenders (including activist psychotherapists) who were working with them, in Latin America (mainly Argentina, Chile, and El Salvador) and to volunteer for periods of about 3 months each with two NGOs: the first, Gono Shahajjo Sangsta (GSS), in Bangladesh, focused on adult literacy, community education, health care, and legal assistance for the poor. The second, Children’s Rehabilitation Center (CRC), in the Philippines, provided counseling and creative arts therapies to children who were traumatized or bereaved as a result of political violence.

After receiving my first Master’s in 1988, I spent six months as a kindergarten teacher at Oasis of Peace/Nive Shalom/Wahat al-Salam, an intentional community located about an hour’s drive north of Jerusalem, where Jews and Palestinian Arabs (both Muslims and Christians) live together as a model of coexistence, and conduct educational workshops on peacebuilding and justice (“The School for Peace”). I went on to pursue graduate study in a combined clinical/community psychology program at the University of Maryland, obtaining a second MA as well as a graduate certificate in women’s studies, in 1993. My second MA thesis, which contained aspects of both disciplines (psychology and women’s studies) focused on the relationship between sexual violence (particularly rape) and self-destructive behavior such as suicide attempts. I presented portions of this study at the 100th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in 1992. My study was chosen for the Student Research Award by the American Psychological Association’s Division of Clinical Psychology (Psychology of Women section) in 1992, and was published in Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior: Special Issue on Gender and Culture in 1998.

I moved to New York City in September of 1993, and completed my PhD in clinical psychology 6 years later. I received a 3-year doctoral fellowship as research assistant to Dr. Beverly Greene, a clinical psychologist who specializes in the role of institutionalized racism, sexism, heterosexism, and other oppressive ideologies in the psychology profession and in the practice of psychotherapy. Dr. Greene endeavors to use psychotherapy to promote psychological emancipation and social justice.

During my years at St. John’s, I was less involved in international human rights work, but I began to develop ways of applying the poetry therapy methods I had learned at St. Elizabeth’s to groups where participants sought to become more aware of the complex dynamics of racism and other forms of oppression and to build bridges across differences of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and culture. I designed and implemented a variety of workshops utilizing this approach, and developed some of my ideas into articles for publication. I coined (and trademarked) the term “graphopoetic process” to describe the non-clinical use of expressive writing and poetry therapy methods to promote cohesiveness and mutual recognition in groups, organizations, and communities.

(For more information about this approach, please refer to my separate website, www.graphopoetic.com.)

In 2002, about a year and a half after completing my psychologist’s license, I reconnected with my professional interest in survivors of ethnic and political violence in my position as clinician for the September 11th Response Project, which was based at a major teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. Together with colleagues, I designed and facilitated support groups for individuals whose loved ones had been killed, primarily on the two planes that had departed from Boston’s Logan Airport, though also with relatives of people who worked in the Twin Towers in New York City and at the Pentagon in Washington, DC.

In 2003, I was given 10 weeks leave to complete a summer postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania’s Solomon Asch Center for Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict. The Asch Center (which has since relocated to Bryn Mawr College) was created to advance research, education, and practice in addressing ethnic conflict and political violence. I was particularly interested in the psychosocial consequences of, and interventions for, genocide and war. One of the special guest lecturers was Dr. Jon Hubbard, a psychologist with the Center for Victims of Torture (CVT), an international NGO with headquarters in Minneapolis.

After completing the fellowship, I received an Asch Center grant to study literary and artistic responses to the Cambodian genocide. The grant allowed me to follow up a 2001 journey I’d taken to Cambodia (in which I’d explored the psychological and cultural aftermath of the Khmer Rouge genocide) with a project to understand the ways that survivors used the creative/expressive/literary arts to “testify”, given that trials for the Khmer Rouge atrocities had not taken place.

Professional Positions in International Human Rights Organizations

It seems fitting that in early 2004, Anastasia White, the daughter of Dale and Tish, with whom I had lived and worked in South Africa nearly two decades earlier, e-mailed me a notice informing me of an opening for a psychologist/trainer with the Center for Victims of Torture’s program for Liberian refugees in Guinea. I applied, was interviewed by Jon Hubbard, and in April 2004 closed down my life in the Boston area and moved to Guinea, West Africa, as part of CVT-Guinea’s international mental health team. I remained in Guinea for a year, after which most of the Liberian refugees had been repatriated and CVT’s program in Guinea drew to a close while a new branch of CVT was launched in Liberia, focusing on reintegration of the repatriated Liberian refugees.

In Guinea, my expatriate colleagues and I were responsible for administering four different community mental health centers for war-traumatized refugees. We provided group, individual, and family counseling for Liberian child, adolescent, and adult survivors of torture and war trauma who were residing in refugee camps in the Albadariah region, a remote region more than 10 hours by road from the capital. We provided live, on-site supervision to Liberian paraprofessional counselors in their assessment of clients and in their facilitation of counseling groups (total of 30 supervisees). We designed and conducted internal trainings for beginning, intermediate, and advanced counselors. We advocated with health-care providers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and UNHCR on behalf of vulnerable clients. We provided training and consultation for community and religious leaders, teachers, lawyers, and health care workers, among others.

On the basis of this work, in 2006 my six team-mates and I were awarded the American Psychological Association’s International Humanitarian Award in Recognition of Extraordinary Humanitarian Service and Activism by a team of psychologists, for the services we rendered to the Liberian refugees in the refugee camps of Guinea during 2004-2005.

(Click to read the award proclamation, which was published in American Psychologist in 2006.)

(To read more about my work in Guinea, please click on the links to these articles. Trauma Healing in Refugee Camps & Healing Power of Symbolization)

(To listen to a radio interview with me, conducted by Minnesota Public Radio in 2006, which focuses on CVT’s work in Guinea, click below.)

I later completed a second year of work as a clinician/trainer for CVT, this time in Jordan, where CVT ran a clinic for Iraqis who had fled torture and ethnopolitical violence in their homeland to seek refuge in Amman. In that capacity, my Jordanian, Iraqi and Palestinian colleagues and I provided individual and parent-child counseling to Iraqi child, adolescent, and adult survivors. I facilitated a total of eight different groups lasting ten sessions each. We designed and conducted two intensive internal basic trainings (lasting one week each) for 12 counselors, on trauma treatment, group facilitation, counseling skills, and related topics, as well as follow-up trainings between a half-day and 3 days (e.g., coping with nightmares). I provided live, on-site supervision to 12 counselors (with BAs, MAs, PhDs) from diverse ethnic backgrounds as they provided care for the Iraqi refugees. I conducted trainings for NGOs, schools, universities, and health-care providers, and also supported the national staff in developing and delivering external trainings. Additionally, my colleagues and I designed and implemented community outreach to generate client referrals and to sensitize the community to human rights issues. We advocated with physical therapists, teachers, medical doctors, hospitals, UN agencies, and other NGOs for the clients’ multifaceted needs.

(To read more about my work in Jordan, click on the links to these articles. From Private Pain Toward Public Speech & Reading and Writing with Iraqi Refugees)

Young Girl on a Mountain Path, Nepal

Photo by Shanee Stepakoff, 1987

All rights reserved

One of my most significant professional positions in the area of human rights practice was the two years four months I spent as the psychologist for the Special Court for Sierra Leone, a UN-backed war crimes tribunal established following a long civil war in which many atrocities had been committed by various armed factions. As part of the Witness and Victims Section (WVS), which was directed by Saleem Vahidy, I was responsible for the provision of psychosocial support for all witnesses. I designed, conducted, and supervised pre- and post-trial psychosocial assessments. I supervised the Court’s counseling team (10 persons, including nurses, psychosocial counselors, social workers, and a student intern). Our team conducted and supervised courtroom briefings to familiarize witnesses with trial procedures. We liaised with schools, vocational training institutes, NGOs, and health care providers to ensure that witnesses’ educational, social, and medical needs were fulfilled. I also designed and implemented a training program to enhance the knowledge and skills of the local counselors; and I designed and conducted trainings for multiple departments of the Court (e.g., investigators, attorneys, etc.) on issues such as gender sensitivity, trauma awareness, child protection, and so forth.

While at the Special Court, I directed a large study of various facets of witness testimony. The study included in-depth interviews with 150 witnesses regarding their perspectives on their experience of testifying in the tribunal, and on the long-term impact (psychosocial consequences) of having testified.

(Click the links to read my articles on the Experience of Testifying, and the Psychosocial Impact of Testifying.)

In another part of this study, based on interviews with 200 witnesses, we explored motivations for testifying, seeking to shed light on the reasons that people feel inclined to speak out publicly about human rights abuses. This article, which was published in the International Journal of Transitional Justice in 2014, is one of the largest studies ever conducted on the motivation to testify about war crimes.

(Click here to read my article on the Motivations for Testifying.)

In another article based on the Special Court research, I compared a witness’s perspective on the similarities and differences between creating and performing in a drama about her wartime victimization with testifying about her victimization in the courtroom setting. (Telling and Showing)

An article of which I am particularly proud was one in which I was co-author with human rights attorney and legal scholar Michelle Staggs Kelsall. This article, which was published in the International Journal of Transitional Justice in 2008, focused on the experiences of a group of women who had wanted to testify about their experiences of sexual victimization but were not able to do so because of a judicial prohibition on sexual violence testimony in one of the four SCSL trials, a decision that caused them tremendous disappointment, confusion, and frustration. The article, in which we juxtaposed what the women had wanted to say with what they were permitted to say, is assigned reading in courses at several universities (e.g., McGill, NYU, Bristol), and has been widely cited in the transitional justice literature. More importantly, this article provided a way for these women’s stories to come to light, stories that would otherwise have been erased from the official history of the Sierra Leonean war.

(Silencing Sexual Violence)

My most recent (and possibly my final) article from this project, entitled A Trauma-Informed Approach to the Protection and Support of Witnesses in International Tribunals: Ten Guiding Principles, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice in 2017, brings together the most important lessons learned from working with witnesses at the Special Court and from the scholarly literature on trauma theory and trauma-informed practice.

During these years, I also had the opportunity to design and conduct short-term trainings on human rights related issues for a number of local NGOs, including the The Center for Victims of Torture (Kenema, Sierra Leone) and the Mending Hearts Program of the Sierra Leone Council of Churches, and I conducted a two-week training for CVT’s Liberia program (in Monrovia and Gbarnga), on torture treatment, gender-based violence, group facilitation, and counseling. I also gave two presentations on refugee issues, at the invitation of the United States Refugee Resettlement Program’s Overseas Processing Entity, operated by Church World Service, in Accra, Ghana. In Cambodia, I conducted half-day trainings on witness support for staff of the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) and for civil society organizations (the latter under the sponsorship of the Open Society Justice Initiative), in preparation for the Khmer Rouge Tribunal.

In 2006, I was given a small grant to cover my participation in an intensive, two-week seminar on Transitional Justice and Peacebuilding, for senior practitioners and mid-career professionals, sponsored by the International Center for Transitional Justice, in Cape Town, South Africa. In 2006, I also spent two weeks in Zimbabwe, conducting a detailed evaluation of the psychological counseling services of The Amani Trust (Counseling Services Unit). Amani/CSU was a Zimbawean human rights NGO that focused on preventing organized violence and torture and providing rehabilitation to victims. My work was part of a larger program evaluation conducted by Adroit Consultants and was supervised by Adroit’s Senior Partner, Harriet Ware-Austin, an internationally recognized human rights expert.

In recent years, as I’ve devoted more of my time and energy to family responsibilities, my professional activities have been focused more on my writing, psychotherapy practice, and university teaching than on international work. However, when suitable short-term opportunities arise, I try to stay connected to human rights practice. By special contract, at the request of Dr. Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, Senior Research Professor in Trauma, Memory, and Forgiveness at the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, South Africa, I coordinated the Sigrid-Rausing Roundtable Dialogues in South Africa in December 2012. This entailed my recruiting and training a team of facilitators to conduct roundtable dialogues between survivors of ethnopolitical violence and psychosocial care professionals who sought to learn about resilience and innovative approaches to healing. I then evaluated the roundtable method and prepared a detailed program report.

In 2016-2017, I completed a Training of Trainers with Gender Equity and Reconciliation International. This program is based on a belief in the transformative power of women and men deeply listening to each other’s experiences and endeavoring to become aware of and challenge the disempowering ways of thinking and behaving that are caused by gender injustice and restrictive socialization practices. GERI is active in several different countries, and after I complete some further advanced training in 2019, I hope to assist in facilitating GERI’s introductory 3-to-5-day experiential workshops a few times per year. I also continue to be involved in anti-oppression training work through my professional affiliation with the NTL Institute.

Click to learn more about Gender Equity and Reconciliation International.

Click to learn more about NTL Institute.

Research and Scholarly Writing

My Publications on Human Rights Issues Are Listed Below.

These include scholarly articles in peer-reviewed journals and chapters in edited books. For some, you can click on the link to read the abstract and/or article.

Stepakoff, S., Henry, N., Barrie, N., & Kamara, A. (2017). A trauma-informed approach to the protection and support of witnesses in international tribunals: Ten guiding principles. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 9, 268-286.

Stepakoff, S. (2016). Breaking cycles of trauma through diversified pathways to healing: Western and indigenous approaches with survivors of torture and war. In P. Gobodo-Madikizela (Ed.), Breaking cycles of repetition: A global dialogue on historical trauma and memory (pp. 308-324). Budrich Publishers.

Stepakoff, S., Reynolds, S., & Charters, S. (2015). Self-Reported Psychosocial Consequences of Testifying in a War Crimes Tribunal in Sierra Leone. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4, 161-181.

Stepakoff, S., Reynolds, S., Charters, S., & Henry, N. (2015). The Experience of Testifying in a War Crimes Tribunal in Sierra Leone. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 21, 445-464.

Stepakoff, S., Reynolds, S., Charters, S., & Henry, N. (2014). Why Testify? Witnesses’ Motivations for Giving Evidence in a War Crimes Tribunal in Sierra Leone. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 8, 426-451.

The Refugee, painting courtesy of Esam Jlilati, www.jlilati.com, all rights reserved

Stepakoff, S., Hussein, S., Al-Salahat, M., Musa, I., Asfoor, M., Al-Houdali, E., & Al-Hmouz, M. (2011). From private pain toward public speech: Poetry therapy with Iraqi survivors of torture and war. In E. G. Levine & S. K. Levine (Eds), Art in action: Expressive arts therapy and social change (pp. 128-144). Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. (Click to read this chapter.)

Stepakoff, S., & Ashour, L. (2011). Reading and writing: Working with traumatic grief among Iraqi refugees in Jordan. The Forum: Quarterly Publication of the Association for Death Education and Counseling: Special Issue on Expressive Therapies in Thanatology, 37, 22-23. (Click to read this article.)

Stepakoff, S., Bermudez, K., Beckman, A., & Nielsen, L. (Editors). (2010). Training Paraprofessionals to Provide Counseling and Psychosocial Support for Victims of Torture and War Trauma in Refugee Camps and Post-Conflict Communities: A Training Manual Based on the First Decade of CVT’s Programs in Africa (Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo). (Limited-circulation training manual created for the Center for Victims of Torture, Minneapolis, MN).

Stepakoff, S., Bermudez, K., Beckman, A., & Nielsen, L. (Editors). (2010). Group Counseling for Survivors of Torture and War Trauma in Refugee Camps and Post-Conflict Communities, Facilitated by Paraprofessional Psychosocial Agents Under the Supervision of On-Site Professional Clinicians: A Manual Based on the First Decade of CVT’s Africa Programs. (Limited-circulation counseling manual created for the Center for Victims of Torture, Minneapolis).

Stepakoff, S. (Spring 2008). Telling and showing: Representing Sierra Leone’s war atrocities in court and onstage. The Drama Review (TDR) (Special Issue on War), 52, 17-31. (Click to read this article.)

Staggs-Kelsall, M., & Stepakoff, S. (2008). “When We Wanted to Talk About Rape”: Silencing sexual violence at the Special Court for Sierra Leone. International Journal of Transitional Justice, Special Issue on Gender and Transitional Justice, 1, 355-374.

Stepakoff, S. (2017). The healing power of symbolization in the aftermath of massive war atrocities: Examples from Liberian and Sierra Leonean survivors. In N. Mazza (Ed.), Expressive Therapies, Routledge. (Originally published in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 2007)

Stepakoff, S., Hubbard, J., Katoh, M., Falk, E., Mikulu, J., Nkhoma, P., & Omagwa, Y. (2006). Trauma healing in refugee camps in Guinea: A psychosocial program for Liberian and Sierra Leonean survivors of torture and war. American Psychologist, 61(8), 921-932. (Click to read this article.)

Stepakoff, S., & Bowleg, L. (1998). Sexual identity in sociocultural context: Clinical implications of multiple marginalization. In R. A. Javier & W. G. Herron (Eds.), Mental health, mental illness and personality development in a diverse society (pp. 618-653). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Stepakoff, S. (1997). Poetry therapy principles and practices for raising awareness of racism. The Arts in Psychotherapy: Special Issue on Cultural Diversity in Creative Arts Therapies, 24, 261-274.

Stepakoff, S. (1987). Detainees in South Africa: What They Experience and How They Cope. Qualitative research report based on Master’s thesis (162 pages). Available at the RCT (Rehabilitation and Research Centre for Torture Victims) Documentation Centre and Library, Copenhagen, Denmark. Cited in the books The Psychological Origins of Institutionalized Torture (by Mika Haritos-Fatouros, Routledge, 2002) and Political Violence and the Struggle in South Africa (edited by Andre du Toit & N. Chabani Manganyi, St. Martin’s Press, 1990). (The citation in the latter book, as well as copies of the report that were circulated in South Africa in the 1980s, contained the pseudonym ‘K. Wrenn’ for enhanced protection of participants’ confidentiality during the apartheid era.)

My Presentations on Human Rights Issues Are Listed Below.

For an extensive list of experiential workshops/trainings I have conducted for human rights workers, please refer to the “Teaching/Training” page of this website.

These are not included in the list below.

The list below contains mainly papers presented at professional conferences.

Stepakoff, S. (2015, Nov). Incorporating Expressive Arts Therapy Approaches in Refugee Mental Health Care: Examples from West Africa and Jordan. Invited presentation at the California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco.

Stepakoff, S. (2014, April). The Power of ‘Found Poetry’ In Contexts of War. Invited keynote presentation at 5th Annual Arts in Healthcare Conference at Lesley University, Cambridge, Mass., Arts and Global Health: Art, Memory, and Testimony in the Aftermath of Trauma.

Stepakoff, S. (2012, December). Breaking Cycles of Trauma Through Diversified Pathways to Healing: Western and Indigenous Approaches with Survivors of Torture and War. Paper presented at conference entitled Engaging the Other: Breaking Intergenerational Patterns of Repetition, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Brenda Hillman, Nick Flynn, Fred Marchant, and Shanee Stepakoff (2010, April). Before, After, Under, Over, Inside, and Beyond the Anti-War Poem (panel). The Annual Conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, Denver, Colorado.

Stepakoff, S. (2009, July). The Utilization of Poems, Proverbs, Stories, and Expressive Writing in Psychotherapy with Iraqi Survivors of Torture and War Trauma – Insights from the First Six Months of CVT’s Work in Amman. Invited presentation for 35 staff of a variety of NGOs providing mental health care and psychosocial support for Iraqi refugees in Jordan.

Stepakoff, S., Hubbard, J., Katoh, M., Falk, E., Mkulu, J., Nkhoma, P., & Omagwa, Y. (2006, August). “And the Blood of the Children Was Like Children’s Blood”: Telling the Truth About Torture and War. Invited Award Address at the 114th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, New Orleans. (Refer to the “Writing” page on this website or click to read.)

Stepakoff, S. (2006, June). The Role of the Creative Arts in Recovery From Genocide, Torture, and War: Examples from Research and Practice with Cambodian and West African Survivors. Conference of the Solomon Asch Center for the Study of Ethopolitical Conflict, Philadelphia.

Stepakoff, S. (2005, December). Guiding Principles of Psychosocial Support for Witnesses at the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Paper presented at special meeting of the Cambodia Justice Initiative, for staff of CJI, Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), and NGOs responsible for the psychosocial care of witnesses for the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Stepakoff, S. (2006, August). Psychosocial care for victims and witnesses in the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Invited paper presented at the National Forum for Trainees in Social Work. National Network for Psychosocial Care (NNEPCA), in collaboration with Institute for Public Administration & Management & Handicap International

Stepakoff, S. (1992, August). Lucretia’s Legacy: The Role of Rape in Women’s Self-Destruction. Paper presented at the 100th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Stepakoff, S. (1989, January). Detainees in South Africa: What They Experience and How They Cope. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Psychological Stress and Adjustment in Time of War and Peace, Tel Aviv.

Stepakoff, S. (1988, August). Tortured Children: The South African Legacy. Paper presented at the 96th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Atlanta, Georgia.